The Guardian : Gerhard Richter review – ‘so disorientating I almost fell over’ (by Adrian Searle)

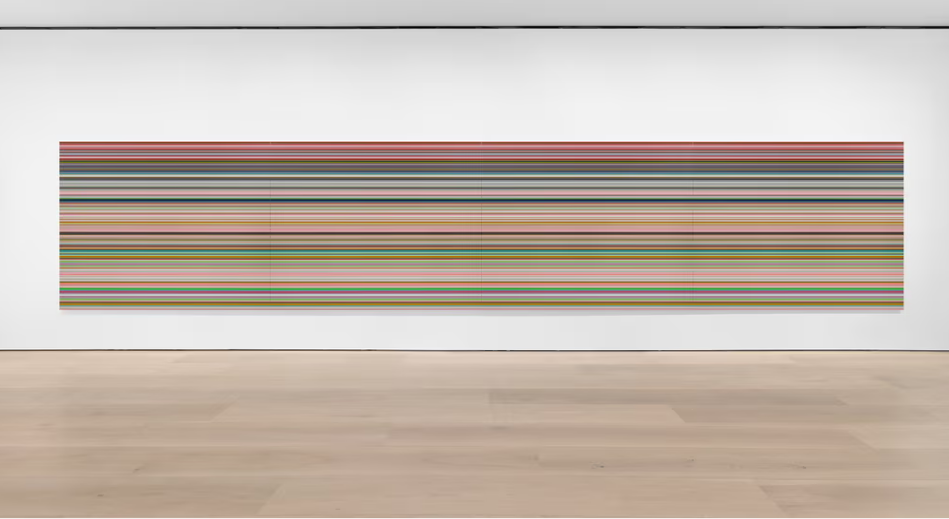

‘Letting the horizontal stripes fill my field of vision, I stood there and wobbled’ … Gerhard Richter at David Zwirner. Photograph: Anna Arca/© Gerhard Richter 2024 (25012024)

Colours fuse and split, curdle, judder and smear in the elusive work of a nonagenarian artist still out to surprise

The strength and pleasure of Gerhard Richter’s work lies in its boundlessness, its variety, its sneakiness, its reliance on inner compulsion and intelligence. Contradictory, antithetical, incompatible: Richter swerves from one way of working to another, in an exhibition that fills two floors of David Zwirner in London. This could almost be a group show rather than work made by a single artist. Richter won’t be pinned down, and he still wants to surprise himself, even as he approaches his 92nd birthday next month.

As is his custom, Richter built a scale model of the gallery in his studio and planned the show to the last detail. The earliest work here was made in 2010, the latest in August last year. Richter is directing us, first one way, then another. Heavily worked and scraped-down abstraction gives way to a highly reflective glass surface that mirrors the room. But behind the glass is a reproduction of one of Richter’s skull paintings, the skull facing to the side and getting caught up with one’s own reflection, along with the other works behind our backs. Another small mirrored exterior reveals impenetrable grey beneath a surface marked with a faint horizontal and vertical line, while upstairs a larger, polished mirror opens up a virtual space beyond our reflections. Here I am, but where am I?

Some Richters you look at, others you look into. Some invite very close inspection while others throw you off in a blitz of racked and scraped back, scabby red. The curdled coagulations and magma-like arrested flows of coloured lacquer, trapped on an aluminium surface behind their glass frames, have an almost gemstone-like quality, geological and liquid, intended but unstable. Something stirs here, a whole world moiling with systems of geological weather. It feels like a deep dive beneath the surface of one of his squeegeed and putty-knifed abstractions, with their disinterred layerings and scrapings. It is hard to see how exactly these smaller works are made. The technique seems to have something to do with monoprinting and the surrealist technique of decalcomania. Colours fuse and split, they slide and conglomerate.

‘Geological and liquid, intended but unstable’ … Aladin (Aladdin), 2010, by Gerhard Richter. Photograph: © Gerhard Richter 2024 (25012024)

An enormous, 10-metre wide inkjet strip painting (Richter calls them paintings rather than digital prints) in the upper gallery at once sucks you in and pushes you away. Letting the horizontal stripes fill my field of vision, I almost fell over. There’s no room to fully back away to see the whole thing head-on, so your view is always either canted or close up. I stood there and wobbled, my eyes slewing along the racing lines. As narrow as a hair or as broad as a finger, the lines of colour offer a multitude of horizons. Some colours attacking, others receding, some like a bass string, others a garotte. The lines are as precise and as taut as a laser, and there are far too many to count. It’s all going on in front of me, down at my knees and over my head, in my peripheral vision and perhaps even in my ears. All this is great, but I can’t take the phenomenological overload for long.

The process of the strip paintings begins with a scan of one of Richter’s own abstract works, a section of it halved and mirrored on a computer, then halved and mirrored again and again until the lines appear. If he kept going with the process he’d end up with some sort of visual white noise. A decade ago, Richter told me that he’d finished making the strip paintings, and also his flow paintings, of which the smaller lacquer-behind-glass works here seem to be miniature examples. He was mostly just moving the paint around till it felt right, he told me then. “My dream is to close the door and paint,” he said. “Small paintings, maybe abstracts, maybe landscapes.” Richter made his last large-scale abstractions in 2017.

Some drawings are unfathomable wanderings, following routes only the artist knows

Whatever else he has been doing, he has mostly been drawing, working with ink and pencil on cheap A4 paper. There are several long runs of these drawings here, each one precisely dated, as if they constituted a diary. His drawings are full of mappings, judderings, contours, weird coagulations, smears and rubbings-out. Sometimes, Richter uses solvent to manipulate the graphite and move things around. There are smudges and glowerings, areas of frottage, contours and horizons. In one, something like a sheep’s head looks back at me, as surprised to see me as I am it. In others, profiled, silhouetted heads are outlined. Ruled lines quarter an indeterminate space, dividing an undifferentiated flatness, like the borders that go this way and that between the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. Here, they demarcate nothing.a

The drawings mix delicacy with weirdness, intention and spontaneity’ … 11.8.2023 (3), 2023, by Gerhard Richter. Photograph: © Gerhard Richter 2024 (25012024)

Some drawings are unfathomable wanderings, following routes only the artist knows or doesn’t care to know, orienteering a space only he can see, following a situationist dérive across a piece of ordinary typing paper. The drawings mix delicacy with weirdness, intention and spontaneity. I find parts of bodies, legs and thighs and something as gnarly as a canker on a tree trunk. Sometimes it is like finding faces in the clouds. The imagination – ours as much as the artist’s – insists on having its way. Caught in the flux between perception and projection, we keep finding things that aren’t there, and missing what’s right in front of us. In his drawings, Richter is a man at a desk with a piece of paper in a pool of light, and that’s all there needs to be.

At David Zwirner, London, until 28 March.

Article published on https://www.theguardian.com