Village Voice : In London, Yoko Ono Gets a Museum Retrospective that Surprises a New Generation (by Duncan Wheeler)

The 91-year-old artist/singer/songwriter made art before her 1960s notoriety, and her participatory pieces keep her relevant.

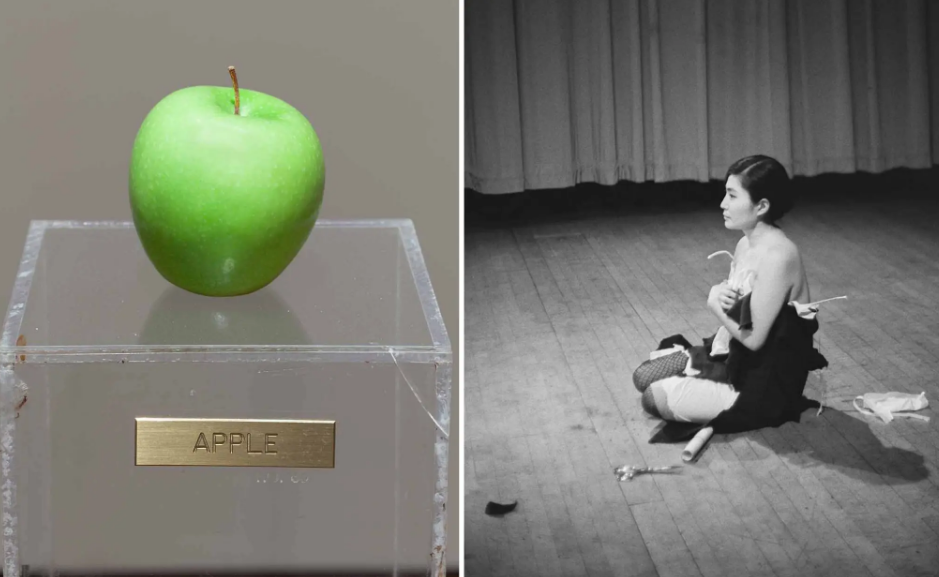

Not-so-forbidden fruit: Installation view of Yoko Ono’s "Apple" (1966), at MoMA in 2015. At Carnegie Recital Hall, 1965: “Cut Piece,” performed by Ono.

Yoko Ono is a global icon and longtime peace activist, but her life has also been marked by violence. Born in Tokyo on February 18, 1933, she was evacuated to the countryside when the U.S. bombed the Japanese capital, in April 1942, five months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1980, Ono’s second husband, John Lennon, was shot repeatedly in front of her as they exited a limousine to enter New York’s Dakota apartment building, which the couple had called home since 1973. Ono and Lennon first met in 1966, when Ono was preparing for the opening of her solo exhibit at London’s Indica Gallery. According to Donald Brackett’s biography Yoko Ono: An Artful Life, the fact that she was not in thrall to Beatlemania was attractive to Lennon, who once claimed that his band had become more popular than Jesus.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, at the Tate Modern, is the U.K.’s largest exhibition of the artist’s work and forms part of a trend, brewing since the late 1990s, of vindication of a woman long vilified as the witch-like destroyer of the Beatles. Peter Jackson’s 2021 docuseries, Get Back, coincided with this broader move questioning the ways that Asian women have been depicted. (The first Yoko Ono album I ever owned was a 2007 collection of her songs remixed and reimagined by young DJs.) Ono was the first female philosophy student at Tokyo’s Gakushuin University, then studied poetry and musical composition at Sarah Lawrence, after moving to New York in 1953. Years before the Fab Four debuted on Ed Sullivan, she was a leading figure in Manhattan’s burgeoning avant-garde art scene, with a debut exhibition in July 1961 at AG Gallery, run by seminal Fluxus artist George Maciunas and gallerist Almus Salcius. Her loft events were attended by legends such as Marcel Duchamp, with whom she shared a deep interest in chess (the installation piece White Chess Set is part of the Tate exhibition), and included performances by future luminaries such as Philip Glass.

An ad from the November 11, 1971, Village Voice: Yoko Ono’s concept piece imagining having a show at the Museum of Modern [F]Art. In 2015, Ono told Artforum she was reacting to the museum's having exhibited very few works by women or Asian artists. She also pointed out, “What I did between 1960 and ’71 seems to have influenced more people than any other periods of my work. But I really don’t know how I survived. Whenever an idea for an artwork came to me, I would act on it. I would get so excited and make the work, and, at the time, it seemed nobody wanted to know. So, I always thought, ‘OK, on to the next idea.’ I’ve gone through life like that; there was never any time to commit suicide or anything.”

Ono’s gift for surrounding herself with talent becomes apparent in the Tate’s roughly chronological exhibition. The ephemeral nature of performance art can be a challenge for curators. (At London’s Royal Academy, the most shocking aspect of a blockbuster 2023 Marina Abramović show was its being the first retrospective dedicated to a female artist in the institution’s 250-plus-year history. Visitors squeezing past a naked couple in one room, an optional sideshow, presented a pale imitation of Ambramović standing naked alongside her then husband in the principal doorway to a museum in Bologna, in 1977, where you had no choice but to push past them to get inside.) At the Tate, visitors are initiated into Ono’s universe through elegantly framed photographs of the AG Gallery opening, shot by Maciunas, along with photos by sculptor Minoru Niizuma of musicians such as John Cage and La Monte Young in Ono’s Chambers Street loft. Ono curated the 2013 edition of London’s annual Meltdown Festival, on the city’s South Bank, during which Canadian electroclash musician Peaches recreated Ono’s Cut Piece (a precursor to Abramović’s performance), in which Yoko invited audience members to cut off her clothes with scissors. Audiences at the Tate can experience a high-quality video recording from 1964 of the original work, performed at Carnegie Hall.

Game of Thrones fans exploring shooting locations in Spain’s rural Extremadura region will likely be surprised to encounter Ono’s sculpture Painting to Hammer a Nail In/Cross Version.

Ono was raised bilingually (her emotionally distant father worked in the U.S. when she was a child), and a wall at the Tate is dedicated to 150 typescripts for Grapefruit, a 1964 self-published anthology of “instruction works.” (The fruit is a recurring metaphor in Ono’s texts and drawings about the melding of East and West.) Gnomic recommendations for a life worth living — “Carry a bag of peas. Leave a pea wherever you go” — will do little to dispel the doubts of those who suspect her of being a charlatan, but her often-ignored sense of humor and ability to translate across borders and cultures ensures that her work is anything but parochial. Throughout the 1960s, Ono was affiliated with Fluxus, an “anti-art” (in the words of founder Maciunas) intersection of performance, experimental art, and handmade objects defined as a transnational tendency, as opposed to a movement. Game of Thrones fans exploring shooting locations in Spain’s rural Extremadura region will likely be surprised to encounter Ono’s sculpture Painting to Hammer a Nail In/Cross Version (2000) outside the Museo Vostell Malpartida, dedicated to the work of German artist Wolf Vostell, who was part of the international Fluxus community. That sculpture is not on display in the Tate, but an earlier iteration, offering visitors the opportunity to hammer a nail into a cross, is. (It was while readying this work for exhibition that she first met Lennon.) Ono and Lennon’s first collaboration, the 1968 “Acorn Event,” centered on planting a pair of oak trees for peace and was part of an exhibition held at Coventry Cathedral in the name of reconciliation, meant to heal wounds caused by the bombing of cities in Germany, Britain, and Japan during World War II.

Activism constituted a logical continuation of Ono’s early performance practices. In 1969, after marrying in Gibraltar, Ono and her new husband staged two week-long “Bed-In” events; the film in the Tate exhibition, Bed Peace, documents the events staged in Montreal. That same year the couple mailed pairs of acorns to world leaders, with the plea that they plant oak trees for world peace. A number of the replies are on display in the exhibition, though they are mainly standard “thank you for being in contact” letters. Although John had changed his name from John Winston Lennon (he wasn’t too keen on being named after Churchill) to John Ono Lennon, the administrators generally addressed their responses in the conventional chauvinist manner of the time, to Mr. and Mrs. John Lennon.

In March 1969, a week after their marriage, Yoko Ono and John Lennon stage a "Bed-In for Peace" in the Presidential Suite of the Amsterdam Hilton.

Ono and Lennon decamped to her adopted city of New York in 1971, revealing the extent to which their union brought him into her world. But the Beatles star was not always a poster boy for egalitarianism. A serial philanderer, according to Brackett, he made Ono write out a list of the men she had slept with, and expected her to make breakfast for him every day. Shortly before his death, Lennon finally admitted that Ono warranted a co-writing credit for “Imagine” — it hadn’t seemed necessary at the time, he said, as she was his wife. In an age when Patti Smith has quietly retired traditional concert set-closer “Rock N Roll Nigger,” heir to Ono and Lennon’s “Woman is the Nigger of the World” (with back-up from Elephant’s Memory, the Greenwich Village street band that also contributed to the Midnight Cowboy soundtrack), it is perhaps not surprising that the Tate chose to bypass that controversial track from the 1972 Some Time in New York City album in favor of projecting performance footage of “Give Peace a Chance.”

Ono’s Bottoms (1966–1967), a 15-minute film composed exclusively of images of the backsides of art-world personages Geoffrey Hendricks, Ben Patterson, Carolee Schneemann, and Yoko herself, is as anodyne in 2024 as it was controversial at the time. The piece would not warrant inclusion in the retrospective were it not for the historical curiosity of it once being banned by the British Board of Film Censorship. The Tate’s publicity materials generally dwell on the interactive nature of the retrospective. In addition to hammering nails, visitors can play an all-white chess game or hop inside a black bag, a reference to Ono and Lennon’s “Bagism” campaign, which mocked prejudice and stereotyping by concealing the physical appearance of individuals through their disappearance from view (an important point in the Instagram age). I was, however, taken aback by how taken aback younger visitors, who threw themselves into Ono’s participatory art, appeared to be after passing through a curtain to experience Fly (1970), a 25-minute film directed by Ono and Lennon that follows the insect protagonist, in real time, as it crosses the naked, honey-covered body of actress Virginia Lust to a soundtrack of Ono’s breaths and gasps, orgasmic and oneiric in equal measure. The reactions of those viewers, a number of whom made a quick embarrassed exit back through the curtain and avoided my eye, brought to mind the scene from Midnight Cowboy, in which the out-of-town Texan stumbles into a party full of Warhol superstars and adopts a goofy embarrassed smile, having no idea how he is meant to react.

Ono’s “Add Colour (Refugee Boat)” (2016), at MAXXI Foundation.

Similar reticence is manifest in the closing installation, “My Mommy is beautiful,” where visitors are invited to write their thoughts or pin a photo of their mother to a vast canvas. With a few exceptions (“I feel guilt many have lost their mothers and mine is still alive, but she consistently hurts me, my sister and dad”), the laudatory tone of most of the messages contrasts with Ono’s lack of sentimentality. Believing her mother to care more about material obsessions than about having a daughter, Ono has admitted to fantasies of being an orphan, and she encouraged Lennon to address through art the trauma of losing his mother as a teenager. Following the birth of Sean Ono Lennon, their only child together, in 1975, Lennon became a stay-at-home father while Ono established herself as a successful and versatile businesswoman. Assisted by Sam Green, a New York dealer she’d known since her Fluxus days, she amassed a formidable art collection, including paintings by Basquiat and Warhol. (Ono and Lennon also took full advantage of tax breaks for dairy farmers, buying cattle in upstate New York in 1977.) The now 91-year-old Ono has consistently proven herself to be a woman of “wealth and taste.” After Lennon’s death, she put some of their belongings on sale; in a diary entry on June 7, 1984, Andy Warhol, no opponent of commercialization, wrote: “Yoko Ono’s having a sale at Sotheby’s but it’s all junk — Art Deco jewelry she’s had lying around and, you know, toilet paper that John touched.”

The Tate retrospective is as comprehensive a show as Ono is likely to receive in this lifetime, and for that the museum should be applauded, having delivered a personal and professional portrait of one of the culture’s major players of the second half of the past century.

Article published on https://www.villagevoice.com