The Arts Desk : A Century of the Artist's Studio, Whitechapel Gallery review - a voyeur's delight

The desire to peek behind the scenes is satisfied,delightfully

by Sarah Kent.

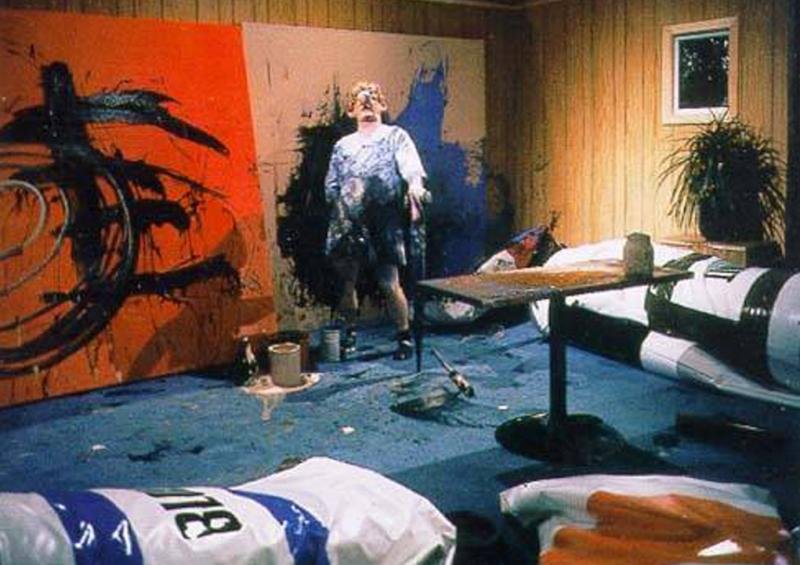

Video still from "Painter", 1996 by Paul McCarthy.

The Whitechapel Gallery's exhibition opens with Cell IX, 1999 (pictured below) one of the wire cages that Louise Bourgeois filled with memories of her dysfunctional family. This one contains a block of marble carved into hands. A tender portrayal of the mother-daughter bond, it is under scrutiny via three circular mirrors.

The sculpture embodies Bourgeois’s dilemma as an artist. While paying tribute to her main source of inspiration – her childhood – it also proclaims her need to protect her memories from prying eyes. Once, when Alan Yentob probed her with questions for a television programme, she not only remained stumm but held up a sign reading “No Trespassing”.

In referring to voyeurism, Cell IX makes a brilliant introduction to an exhibition whose theme is the artist’s studio, since our desire to peek behind the scenes is prompted largely by hope of accessing the artist’s psyche and finding out what motivates them.

William Kentridge sends up this desire in an absurdist video in which he interviews himself (pictured below). In reply to idiotic questions about his artistic aims and ambitions, he smothers a sheet of paper in ink and attacks it with a drill while the interviewer declares “He’s not saying anything interesting!”

The idea of the studio and what it represents is explored every which way in the downstairs gallery. Hans Namuth’s famous 1951 film of Jackson Pollock painting on glass outside his studio promotes the myth of the artistic genius for whom painting is an existential performance – a direct outpouring from the psyche.

Renoir once claimed he painted with his prick. And Paul McCarthy’s wonderfully insane film Painter, 1996 (main picture) takes the piss out of any such macho posturings. Looking like a hobbit, with false ears, a blobby nose and rubber glove hands, he bumbles around the studio assaulting giant paint tubes and canvases with an enormous phallic brush before rampaging like a five year old round his dealer’s office, whining about not being paid.

In February 1996, Tracey Emin exposed to view her naked body and the creative process during a two week residency in a Stockholm Gallery. Viewers could watch her through fish eye lenses, either making paintings of nudes or resting in life model poses. On show are photos of her at work in this temporary studio, where the role of model and artist became fused.

Declaring that “if I was an artist… everything I was doing in the studio should be art”, Bruce Nauman also performs for the camera. He tests his theory to its limits by endlessly repeating banal dance steps that defy classification. Andy Warhol similarly challenged ideas about artistic choice and integrity by leaving a film camera running in the Factory for hours on end. In the clip on show, Nico and the Velvet Underground wander about preparing to perform.

In the 1920s, Kurt Schwitters began building an art installation that gradually took over his entire house in Hannover and a section of his Merzbau now transforms a corner of the gallery into a labyrinthine sculpture. In 1985 Gregor Schneider began turning his family home in Rheydt, near Mönchengladbach into a maze of corridors leading to joyless rooms which he recorded in dystopian videos.

Women artists have often had to make do with working on the kitchen table and in a gesture of defiance, Martha Rosler turned her kitchen into a studio. In her film Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975, she demonstrates the uses of cooking utensils, such as an ice pick, grater and knife, as weapons in a culture war demanding that women and their work be taken seriously.

In the early 1970s, Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow left her studio to experiment with attaching bits of chewed gum to pieces of concrete or wood. She then photographed the results so that all sense of scale is lost and the insubstantial trifles appear monumental. “Creation lies”, she said, “between dreams and daily work.”

In Darren Almond’s video of his empty studio, the passing of time is marked by the loud ticking of a digital clock. The studio is presented as a sterile place that seems to promise nothing but fruitless hours of inactivity. But Almond also photographed the pile of rags on which the painter Lucien Freud wiped his brushes. In his elegiac picture, the rags resemble burial cloths or bandages smeared with blood, and painting is cast as an act of heroism. And in Paul Winstanley’s immaculate paintings of empty art schools, the studios seem to hold their breath while awaiting the arrival of students to enliven the deathly calm.

After so many thought-provoking explorations of what the studio represents – as a metaphor and in reality – the exhibition suddenly fizzles out into boring predictability. The chaos in which Frances Bacon worked is legendary, but a photograph of his studio augmented by a few scattered bits of paper fails utterly to recreate its ambience. Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Kim Lim get similar treatment with tributes that do little to further one’s understanding of their practice.

The only revelation comes in a photo of the shack in Novia Scotia that, in the 1930s, Maud Lewis transformed into a total work of art by decorating every inch of the building and its contents with paintings of flowers and birds. She also painted pictures of local scenes, which she sold to friends for $2 a piece. She was too poor to have a studio, so she turned her whole world into a painting. What an inspiration !

Article published on https://theartsdesk.com