GoCritic! Feature: The benefit of the doubt - Four routes into the work of William Kentridge

Four GoCritic! participants have covered the William Kentridge retrospective at Animafest Zagreb. Tutor Jessica Kiang introduces them and their texts

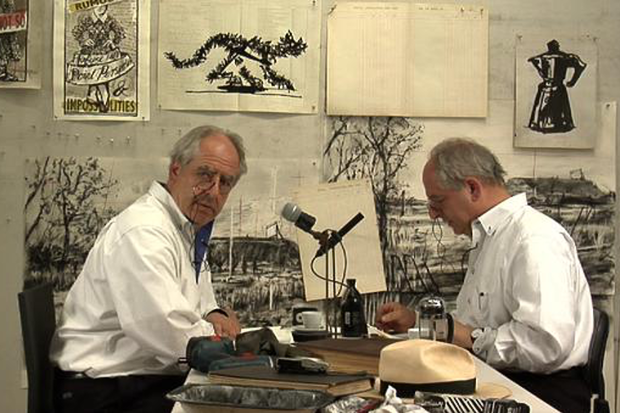

Drawing Lesson 47 (An Interview with the Artist)

Tuesday morning last week, five strangers from across Europe gathered in a Westin Hotel conference room. None of us – the four GoCritic! workshop participants and me, their so-called mentor – had met before, and none of us, to our embarrassment, had much acquaintance with the work of multidisciplinary artist William Kentridge, Animafest Zagreb's chief honouree. In a spirit of trepidation and barely thawed unfamiliarity, then, we trooped along to watch the Kentridge retrospective that afternoon. Nine eccentric, intimidating and inspiring short films later, we emerged, and because I have a sadistic streak, the first exercise I set was for each of them to write a short review of the densely allusive, complex but immensely rewarding films they had just seen. They had 90 minutes.

An hour and a half later, I had four texts, which, in edited and polished-up form, are what we have below. I can't overstate how impressed I was with these pieces, and how proud I am that they represent four such distinctive and valuable entry-points into a vast, endlessly revelatory canon. At his subsequent Masterclass, Kentridge spoke about his artistic approach, one aspect of which is to "give the image the benefit of the doubt." Critics' workshops such as this one exist primarily, to my mind, to give talented emerging critics the confidence to develop their individual voices – you could say, they exist to allow young critics to give themselves the benefit of the doubt.

Here, then, are four stellar examples of what can be achieved by following Kentridge's creative advice, yielding four routes into his work. May you never find your way out.

– Jessica Kiang, Film Critic, Programmer and GoCritic! Animafest Zagreb 2023 Proud Mama

Second-Hand Reading

Joburg Express

by Dinko Štimac (Croatia)

Zagreb, June 6th 2023, 15:30. A train pulls into Student Centre hall at Savska cesta 25. This engine comes in hot, hauling nine short films from South African artist and animator William Kentridge. It's a retrospective that could seem too intense at first, given the sheer quantity of films and their complexity in structure and theme. But if we just climb onto this express line, relax and take in as much of the scenery we can, the journey through Kentridge country will reveal itself.

It starts in Johannesburg – according to one of his titles, the "second-greatest city after Paris." The first three films are deeply rooted in the city, which Kentridge portrays as a place built and fuelled by the hard labour of a nameless working class. His smudgy charcoal technique produces shadows and waves in the wake of the workers’ movements, so their actions are not fleeting, but leave behind a visual record of exploitation, exhaustion and repetition. This is also a form of artistic accusation, amplified by grave, eclectic musical accompaniment: Kentridge purposely isolates and consecrates the underground toils often ignored by official history. Scenes of horror erupt sporadically – some, like the mass shower scene, reminiscent of Holocaust imagery – as if to give voice to long-unheard cries: We were here, look at us, don’t deny our existence.

From the historic, the forgotten and the ignored, the Kentridge train then moves into the land of the meta-textual. In the humorous Drawing Lesson 47 (An Interview with the Artist), Kentridge conducts an interview with himself about art. Interviewer and interviewee are at odds, with one taking the position of artist and the other of producer, facilitator and sometimes censor. Their conflict is hardly even: the producer mutes the voice of the artist, interrupting him, putting words in his mouth, until, in the end, the two aren’t even looking at the same artwork. This terrain is so radically different from the sombre landscapes of earlier as to induce disorientation, yet it also promises even greater abundance the next time you ride these rails. Taking the same route, in this case, is never going to result in the same journey.

Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris

Erasure

by Alen Golež (Slovenia)

There is an almost overwhelming expressivity in the works of artist and animator William Kentridge. From the very first frames of his earliest films, his style can convey the heaviest of atmospheres. The densely drawn lines that make up his figures and environments, and the glowering grey-scale of his charcoal strokes contribute to a sense of hopelessness. And the very use of charcoal as a medium calls up images of dusty coalminers suffering in sunless tunnels, even before such miners become his subject. Charcoal is tactile too, giving Kentridge's imagery a rough and dirty, subterranean texture. And although the working-class archetypes he portrays are static and sombre, his style, full of shifting lines and smudges, presents their bodies as filled with unrest, transforming otherwise inactive individuals into a collective vision of constant, helpless struggle.

A ghastly hallucination of alienation and fatigue soon manifests through another idiosyncratic technique. Instead of animating cleanly from frame to frame, Kentridge erases parts of his illustrations on the spot and draws over them to create a sense of motion. In this way he makes erasure central to his aesthetics. On a metaphysical level that parallels his formal approach, erasure becomes a prerequisite for the flow of time, for movement and for change – for animation itself.

But while the suffering depicted is therefore inevitably fleeting, its intensity consigned to the past, there is an urgent political dimension here too. The historical erasure of the working class by their capitalist overlords, and of the Black experience by white elites, echoes like the screams of the exploited through the physical erasure of the drawings. And this is a purposeful process: the repeated movement of the rubber over the layers of charcoal is forceful and determined, creating oppressive push-and-pull dynamics between the past and the present. The smudges that remain visible serve a key function in reminding us that the pain of the past can never be entirely blotted out. Everywhere we look are signs of its imperfect erasure.

Waiting for the Sybil

The Propaganda Problem

by Dace Čaure (Latvia)

The theme that immediately stands out is the director’s concern with worker’s rights. The greedy capitalists who exploit the overworked proletariat are reminiscent of the visuals used by the Soviet state – the fat, piglike faces and even the striped suits have always signified the “bourgeois” businessmen of the lands that were not “saved” by communism. So while the animation style of films like Mine (1991) or Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989) has the audience mesmerised with its fluidity and skill, it is hard to shake the association with propaganda imagery and its inherent untrustworthiness.

However, a closer examination of Kentridge’s work undermines this simple correlation, and offers a far more subversive viewpoint, one predicated on the particular guilt that comes from being a white South African in a country devastated by Apartheid. From this angle, the loaded imagery that can initially look like a glorification of communism — right down to the Stalin and Trotsky masks used in some more recent works – casts a remarkably different shadow. In particular, Kentridge's use of Black African music – often rousing choral works – merged with striking visual metaphors, gives human, and deeply humane form to the plight of the masses under the iron fist (or, in Kentridge’s imagination, the steel coffee plunger) of an indifferent oppressor.

His later works, especially the flipbook-type animations, become gentler and more dream-like, but the haunting music and the forcefulness are still there. Large, bold slogans are thrust upon the unreadable pages of dictionaries, black bodies dance where there were once letters, making the once-important knowledge obsolete. It is the re-rewriting of the history of the oppressed, bringing suppressed truths back to the forefront without wholly erasing the stains of the past.

Oh to Believe in Another World

Underground

by Sven Hollebeke (Belgium)

In his trademark earthy, heavily pronounced charcoal drawings, William Kentridge exhumes the real-life yet dystopian struggles experienced under the Apartheid regime. But his films do more than showcase his evident engagement with worker’s rights. They also emit a melancholic longing for a proper sense of community, as if the act of commemoration is his way of dealing with the collective traumas of a nation divided by class and race.

Addressing these wounds – both physical and emotional – head-on, Mine, which was produced in 1991, three years before the country’s multiracial elections theoretically ended Apartheid, highlights the blatant dichotomy between the obnoxious capitalist and an exhausted, exploited population. Buried deep in the ground, faceless men gather in coal-black barracks – Kentridge portrays the workers as an anonymous mass, but only to highlight the unfairness of a fight waged by the powerless against an oppressive system. In their nocturnal surroundings, the Black-African miners work to survive until their next meal, or their next breath, their turmoil of no concern to the paunchy capitalist above, personified in Kentridge’s recurring character of Soho Eckstein.

Mine

The mines are Eckstein’s playfield, as becomes evident in ever-transforming drawings that make them mere extensions of Eckstein's desktop workspace. Everyday capitalist that he is, Eckstein casually calls for coffee and smokes his enormous cigar in bed. In a mesmerising sequence that speaks to Kentridge’s vividly imaginative style, the coffee-pot plunger becomes a drill carving an underground route through lifeless bodies and tormented faces suspended in the endless mud. Eckstein might be a caricature, but the towering power his tiniest gesture holds over thousands of men feels frighteningly real.

Kentridge’s sketches are in a constant state of flux. Erasing, altering and straight-up manipulating his drawings, the artist seeks a balance between memory and (un)willing amnesia, as if saying we must destroy to become renewed, yet we must also remember in order to move on. You can feel he’s torn by multiple issues deeply embedded in South African society, seeking to acknowledge both the possibility of an equal social co-existence, and the unattainability of such a utopian ideal, when trauma undermines the ground beneath our feet.

Article published on https://cineuropa.org