Financial Times : Three Iranian women fighting for artistic freedom (by Victoria Woodcock)

Shirin Neshat, Nazy Nazhand and Sheree Hovsepian’s friendship is seeded in their heritage — and has bloomed through their work

There just aren’t that many Iranian women in the art world,” says Shirin Neshat, the 66-year-old artist whose work in photography and film over the past 30 years has attracted acclaim and controversy in equal measure. Talking with her friends, art adviser Nazy Nazhand and artist Sheree Hovsepian, she adds: “I think that the connection between the three of us is that we feel kind of rare in this community. We each play a role.” All three women were born in Iran, but moved to the US in the 1970s and ’80s. In 1979, following the Iranian Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini established the Islamic Republic of Iran. The regime immediately imposed severe restrictions: on freedom of speech, freedom of religion and the rights of women, who were forced to veil, restricted on their employment prospects and forbidden from taking part in activities such as dancing or singing. This year alone, more than 600 executions have been reported in Iran, according to the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights. Neshat, Nazhand and Hovsepian rail against these injustices and support unheard Iranian voices.

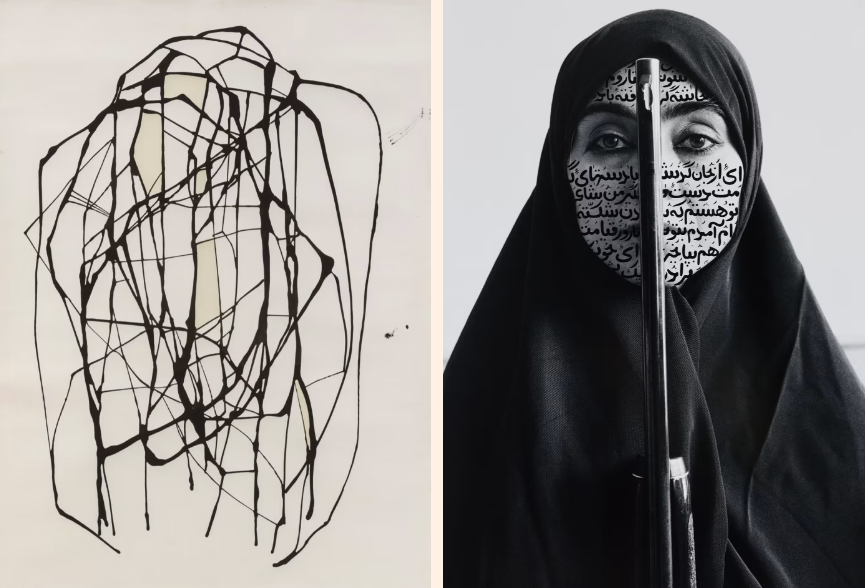

Untitled, 1996, by Shirin Neshat © Courtesy of Shirin Neshat and Gladstone Gallery

Neshat challenges Iran’s oppression of women — her seminal Women of Allah series, created between 1993 and 1997, brought the issue to a global audience. Many of her black-and-white photographs, including close-ups of eyes or hands, are superimposed with handwritten text in Farsi, including words from the late Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad, to signify strength in the face of oppression. Social media has the power to mobilise . . . It’s our duty to make some noise Since her first solo museum show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1998, her work has been featured in major exhibitions and film festivals, from Venice to LA, Amsterdam to Montreal. “Every time there is some kind of political upheaval in Iran, a lot of Iranians expect that I express my solidarity with the people,” she says of her role as a prominent critic. She is an active supporter of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, which was sparked in September 2022 when 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in custody after having been arrested in Tehran for allegedly not complying with the country’s hijab regulations. The subsequent protests — which witnessed women burning the hijab and cutting off their hair — reverberated internationally.

Art adviser Nazy Nazhand at Shirin Neshat’s studio in Brooklyn, New York ; Portrait of Shirin Neshat © Jeff Henrikson

Neshat and Nazhand got to know each other during an earlier uprising: the 2009 Green Movement, sparked by the Iranian presidential election. In the decade that followed, Nazhand established a collective to promote emerging artists from the Middle East. “Connecting with my culture sometimes comes into my work, but it’s also personal, part of my identity,” she says. She has been influential in placing Hovsepian and Neshat’s work in private and institutional collections. Next year, she launches the Nazhand Art & Culture agency; she singles out “the amazing creatives . . . who have been using their voice to speak out on behalf of Iranians fighting for their freedom in Iran”: Tala Madani, Farshad Farzankia, Salar Ansari and Arian Moyaed. Hovsepian’s husband, the artist Rashid Johnson, connected the trio when he introduced his wife to Neshat. “When we met, I felt like we’d known each other for a long time,” says Neshat. Hovsepian had first encountered Neshat’s work as a photography student in Ohio. “Seeing Women of Allah totally changed my idea of what art can be and how someone like me could have a voice within the [art world],” she says.

Pastiche, 2022, by Sheree Hovsepian

Artist Sheree Hovsepian © Jeff Henrikson

Today, her own artwork incorporates black-and-white photography, homing in on different parts of the female form. The final collages — their disparate elements held in dramatic tension with string, nails or ceramic — were exhibited at Frieze London last year by Rachel Uffner Gallery and are currently on show in Making Their Mark: Works from the Shah Garg Collection in New York. “I focus a lot on the body; when I was growing up I was always hyper-aware of my physicality, my difference, of how I move through space,” she says, adding that the personal is also political. The photographs are often of her sister and their fragmented nature can be read as a comment on how women’s bodies are sites of control. “We all carry our connection to our homeland in different ways,” says Nazhand, whose family left Iran as refugees in 1985, in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war. Adds Hovsepian: “We have commiserated about how our parents suffered deep trauma as a result of leaving Iran and the life they knew. In my case, my mother’s sense of displacement deeply shaped my life.” Today, Neshat is exiled from the country where much of her family still lives. “I tune in to the news about Iran on a daily basis — especially since last September,” she says. “I am someone who is unable to disconnect from Iran in a literal way.”

Untitled, 2022, by Sheree Hovsepian ; Rebellious Silence, 1994, by Shirin Neshat © Courtesy of Shirin Neshat and Gladstone Gallery.

It is important to be able to offer advice and feedback to young artists in Iran. “For those of us who are outside [of Iran], we have nothing at stake, and so we feel guilty, and yet we want to help; it’s extremely complicated,” says Neshat. She gives the example of Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi, who was recently jailed, with a death sentence possible, for supporting the anti-government protests. Neshat posted about the trial on social media. “It’s been proven: the more international attention there is, the greater chance there is that a person will not be executed,” she says. “I’m a strong believer that social media has the power to mobilise people. It’s our duty to make some noise.” Since then, Salehi has been released on bail. Making a noise is fraught with challenges. Last October, following the death of Mahsa Amini, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin unveiled a banner of Neshat’s work on the building’s facade, aiming to draw “attention to the current protests in Iran calling for democracy and women’s rights”. But the image of a woman in a hijab also sparked criticism at a time when women in Iran were defiantly burning their headscarves.

“You’re damned if you’re quiet and you’re damned if you say something,” says Neshat. “My work is always very politically charged, but it allows the audience to make their own interpretation.” She remains undeterred. This October, 16-year-old Armita Geravand died in Tehran following an alleged altercation with morality police. The same month, Neshat’s latest video work, The Fury, aired in London at Goodman Gallery and the London Film Festival. “It’s about a woman who is assaulted in prison in Iran,” says Neshat of the two-channel video that dramatically prefigures the Women, Life, Freedom movement. It is currently on show at Fotografiska in Stockholm (until February 2024).

Earlier this year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to incarcerated Iranian activist Narges Mohammadi for “her fight against the oppression of women in Iran and her fight to promote human rights and freedom for all”. “Many people in Iran think of her as a potential contender for a future president,” says Neshat. “My feeling is that maybe art is the best way of expressing my views.”

Iranian artist activists

Soheila Sokhanvari The Iranian-born British artist’s paintings are inspired by Iranian miniatures. Those on show at The Heong Gallery in Cambridge (until 4 February 2024) depict women singers and actors who are no longer allowed to perform under the regime, as well as family and friends.

Arghavan Khosravi The Iranian-born American artist “uses the style of Persian miniature painting to express themes of freedom, exile and empowerment”, says Hovsepian. “But also check out Hamzianpour & Kia gallery in Los Angeles; it has a roster of mainly Iranian artists.”

Farzaneh Forouzesh “She’s a great Iranian video artist who I recently discovered,” says Neshat. Her first film as a writer, producer and director, And her sleeve wet with tears, is an exploration of personal desire in the face of oppression.

Ali Banisadr Brooklyn-based Iranian artist Banisadr spent the first 12 years of his life in Tehran and used the sounds of war to conjure colours and forms in his early work. His recent show of paintings at Victoria Miro’s London gallery reflected present-day events in Iran.

Article published on https://www.ft.com